Dialogue: How much? With whom?

With whom should we try to engage in fruitful dialogue? And how much do we expose ourselves?

The world is scary. Some might say, "on fire" or burning. It burns to touch. (And all this on top of a shaky insight into reality.) How can be address the fire today without getting so burned that we not only miss out on fun but also can't address the fire tomorrow. I am assuming, that you, as I, do not want to sit back and watch the world burn.

You know me. I encourage fruitful dialog. Any two might be able to find common ground, understand each other better, and even learn from each other. This involves a two-way conversation.

Hold Up!

I hear many of you feeling tired of talking. And you might feel like I am encouraging people to sit down and have a coffee with that evil person in our history.

I think, perhaps, you misunderstand my position here. Or maybe you do understand, but fruitful dialogue is not among your goals.

Please let me explain.

Map of Dialogues

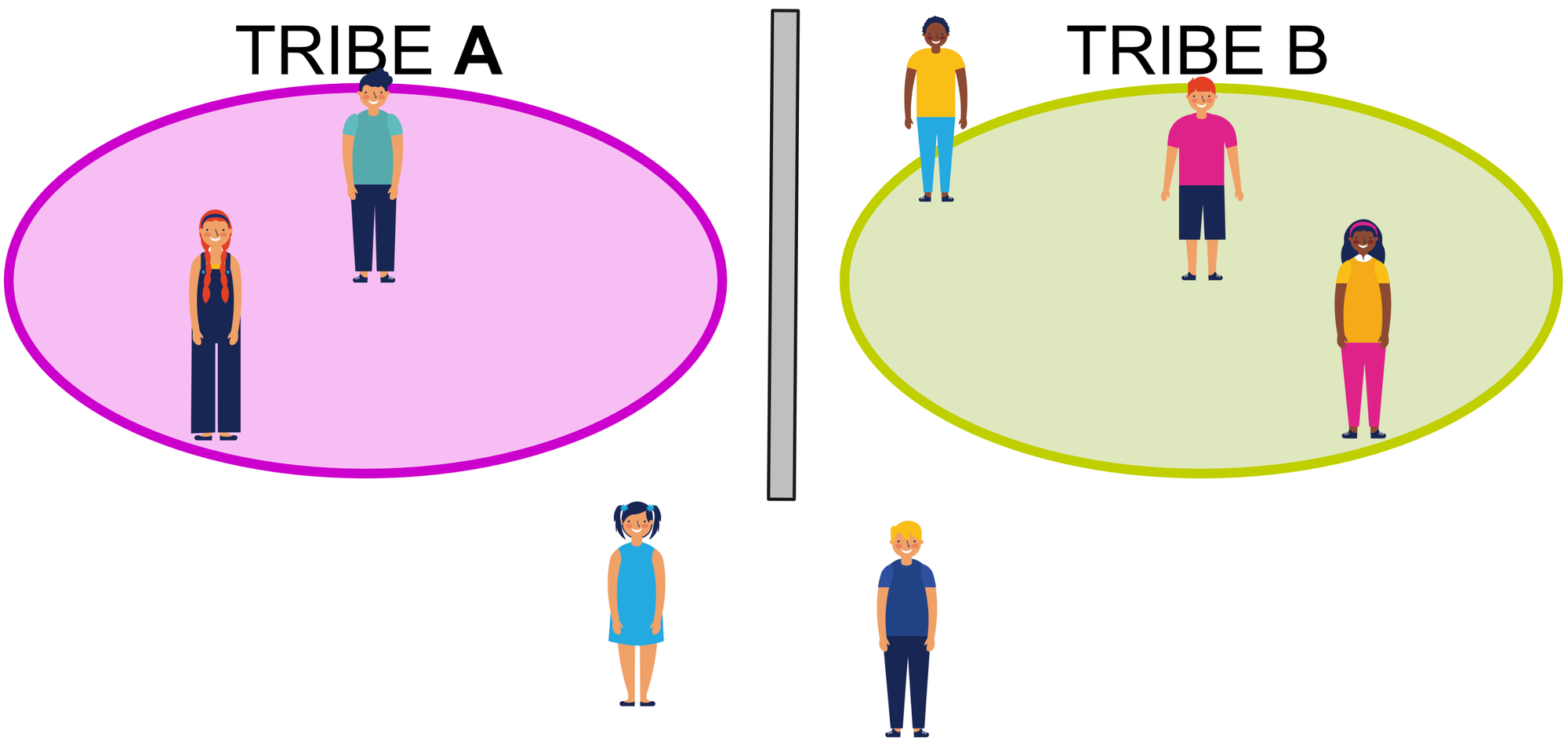

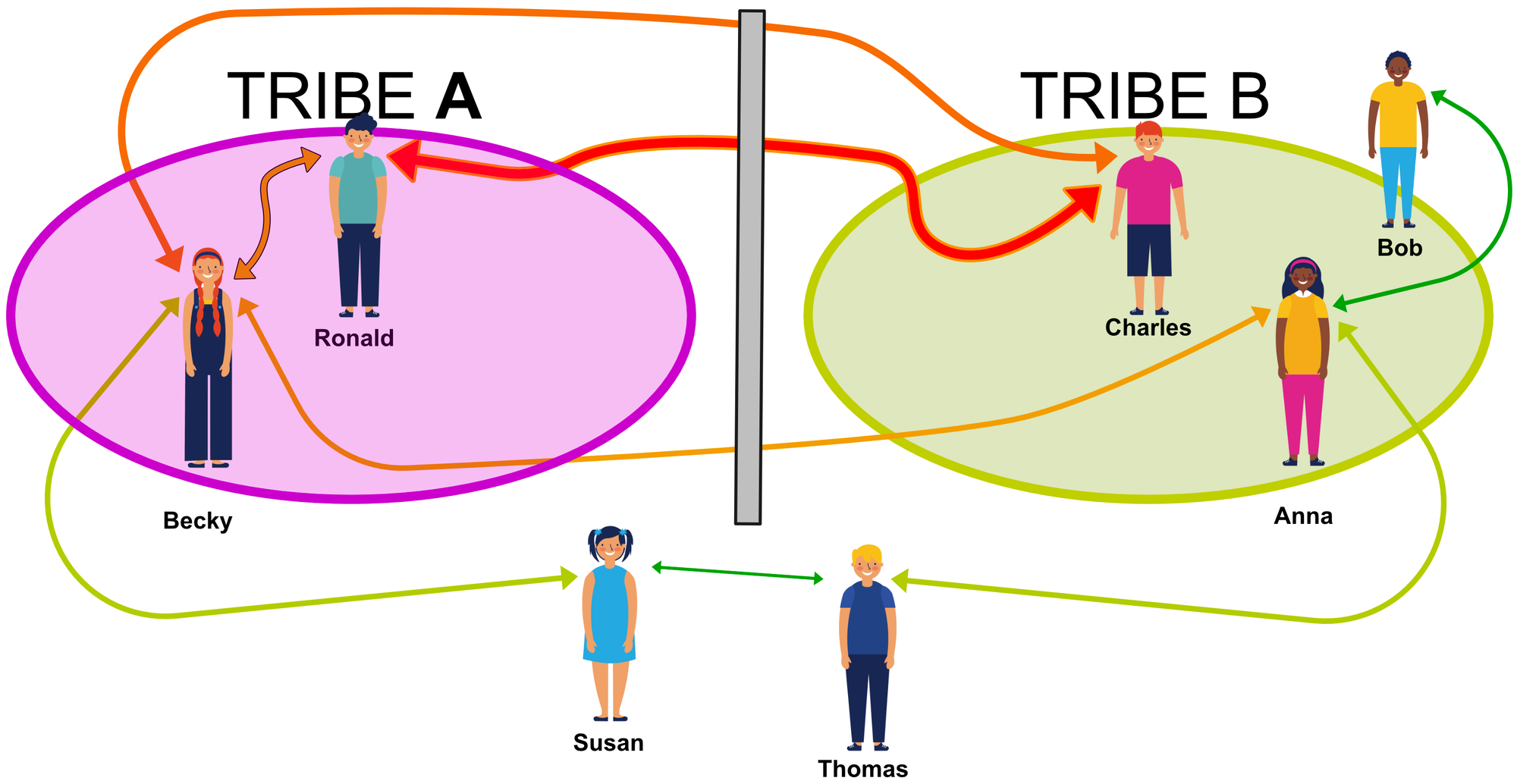

Suppose there two groups in a tribal uproar. The hot-pink vs the orange, let's say. There are some people who self identify as being in the tribe, some of whom see themselves as core and they have solid and confident beliefs (which might lead to arrogance and self-importance). And there are some who do not identify with either group.

There is potential dialogue among those representative people.

Perhaps the easiest dialogue would be between Susan and Thomas, the outsiders. But, maybe one or both are not really outsiders.

It gets harder to communicate as we explore these pairs: Anna and Bob are in the same tribe, so maybe they can relax and communicate. On the other hand, Becky might dislike talking to Ronald because she sees him as extreme and she doesn't always understand what he means. Becky and Anna will likely have trouble talking at first, worldview and vocabulary might conflict, but there is hope. That would be better than Becky talking to Charles a diehard member of tribe B. Of course, Ronald and Charles might understand the other well, but they must maintain the fight. Not shown is Susan or Thomas talking to Ronald or Charles.

And then there is the length and vulnerability of the conversation. Becky and Susan might be able to talk a while and share some things. Becky and Anna might limit durations and scope of conversation at first. Becky might decide that she doesn't have the conversation skills or the emotional intelligence to talk to Charles of Tribe B. She might just not want to; why touch the hot stove and get burned again.

Depth

Suppose Becky is a clerk at a store that Anna or Susan visits. Look at the illustration above.

Becky checks out the few items that Anna bought. Discussion is mostly utilitarian, but Becky says, "I like your collar necklace; I have not seen that before." To that, Anna smiles and says, "Thank you. It is a Kelune; my mother-in-law gave it to me the night before my wedding." She doesn't get into the tradition behind it.

This is a limited opening up. This is limited by the environment, respect for time, and perhaps lines drawn for privacy. All that is OK.

Now, suppose Becky does recognize recognize the name Kelune. She knows from information from sources in Tribe A that a Kelune is bad. Susan is next in line and Becky blurts out in a secretive voice, "I can't believe she wears a Kelune in public."

Here Becky's normal friendliness is overwhelmed by the need to assert the position of Tribe A and the disgust of that Tribe A for those in Tribe B.

Susan (not in either group) decides against complementing Becky on her hair. She keeps here responses short and minimal to avoid any more of that A vs B diatribe.

Yet, that night takes a turn.

That night, Susan, the one who doesn't not identify with either group, attends a book club meeting at her friend's house. She had never been before and finds the people friendly and the environment comfortable. However, Becky shows up and Susan becomes a little more reserved. Surprising to Susan, those in the living room welcomed Becky.

In the discussion of a certain passage in the novel being discussed, Becky started crying, mostly in hurt but a bit in rage. Others gathered to comfort her. Susan's friend asks Becky, "Is it something in this section that affects you so?"

Becky points at a page in the novel and says, "You all act like she is so good. Maybe she is, but she is just pretending. We don't know what the author does not say. It is like she is a Kelune Loonie. She doesn't have to flaunt it! She is arrogant! She is mean. She is selfish."

Susan is not comfortable with this growth of anger.

As others start to say something comforting, Becky looks down and says, "I am lonely."

Susan stares at Becky with a growing understanding and compassion. In her heart she says to herself and to Becky, "I am lonely, too."

Of course, we are curious about this mysterious world. But, let's focus on what is happening in how deep discussion goes. Will Becky and Susan eventually engage in fruitful dialogue, finding common ground, learning about each other, creating good ideas and goals in common?

Are you ready?

There are some conversations we are not ready to have. I know I'm not ready to be a hostage negotiator. Some conversations are thrown upon us, though. I hope if circumstances throw me into that role, I would muster up all I can to perform that and take care of me at the same time so I can complete the task.

What are the factors? If the hostage negotiation is outside our skill range and our desires, then what is inside?

Cognitive Load

In conversation we are loaded with clear thinking and with emotional responses.

Communicating takes a lot of thinking. And if memory does not help, then it is even more a problem. A single phrase can trigger multiple tracks of thought. If we are not careful, good thinking fails.

Motivated reasoning (seeing only identity supporting evidence) can reduce cognitive load, but in a harmful way. To take on a bigger load in thinking can be good. But that means budgeting thinking and duration.

What can we do? Improve knowledge, especially that of the worldview of the other including what they think important words do. Improve cognitive skills, especially in recognizing what is important in what the other is say; exercises help.

Emotional responses, especially when one does not have the mechanisms to handle those, use up cognitive power. On top of that, it moves resources from the clear thinking part of the brain.

What to do? Start with personal reflection. Learn about humility and see whether you can adopt it. Learn about your values and your real self. Set actionable limits. Identify your important identity points; that lowers the surprise. In preparation, lower the activity of the vagus nerve by a simple breathing exercise. A short exercise exercise of 4-counts breathing in, 6-counts breathing out is often recommended. Set conditions: time of day, order in day, physical setting, duration. Consider hydration, sleep and food. Prepare to be wrong.

Be ready by preparing, breathing, relaxing. Engage well. Recover with a walk in nature with a good friend.

In both cases, brain load or emotional smack to the head, we go stupid. But, we can learn to minimize that.

Cognitive Exhaustion

Let's contrast load and exhaustion.

Cognitive load is what happens during the conversation—working memory is maxed out, deep memory communication is bounded, multiple tracks running at the same time.

Cognitive exhaustion is what happens afterwards. It is usually called cognitive recovery, emphasizing that you will recover. I call it here cognitive exhaustion, recognizing that you are beat; this takes something out of you.

This period of exhaustion, often overlooked in the science of discussion, is real. You know it is when you feel it. It has taken away from much of your day. Conversations can be expensive.

Just as there are two types of cognitive load, there are two overlapping ways we get exhausted.

Resource Depletion

Skipping the neuroscience and psychology, let me say that brain and thinking resources get depleted and need time. Even when thinking is not in the area of discussion, similar parts of the brain might be used.

This is not to be avoided in all cases. Trying to see the full picture is hard and is exhausting. But working hard for what is important to us can be good. The important thing is to start out with the easy and move to the hard. Prepare for the hard. Plan for a recovery time. It is part of the fruitful dialogue process.

High Emotional Stress

Stress hormones have a recovery curve. During this time, your threshold for further stress is lower. Your mood is affected, your ability to think clearly is reduced, and you feel weary, even in a fog.

In recovery, not try to repress this. Do this instead:

- Immediately engage in physical movement such as a walk or scrubbing

- Enjoy nature

- Chat with a safe person

- Have a good night's sleep

- Schedule recovery

You have a real but limited capacity that can be grown over time. Managing this wisely in preparation, engagement and recovery is what sustained fruitful dialogue, rather than heroic and unsustainable.

Which conversations? With whom?

We have limited resources. Some topics are more important than others. Some individuals are not ready for conversation. Even with channels of communication, we must use discernment.

Not available

Some conversations are effectively impossible right now when there exists...

- Active threats

- Intoxication and drug use

- Psychotic and delusional states

- Performance for an audience

Not for you

This might be harder. The channel exists, both you and the other are neurologically capable, the above conditions do not hold, but the specific relationship between you and the other makes it impossible, maybe the identity of one triggers the other, maybe you represent something that makes it impossible for the other to hear you.

I mentioned hostage negotiation above. Sometimes negotiators have to rotate. This is not some failure; this is normal. The interpersonal chemistry is not working. Recognizing you are not the right person is not defeat; it is discernment.

All systems go

There are times you can talk. How do you know?

Let's look at it.

Indicators for stepping away

There are patterns that indicate a withdrawal is needed or engagement should not be taken. For now.

- The other is consistently (several times) redefining words mid-conversation—not because they are confused, but because holding a fixed meaning would require engaging your point.

- Every concession you make is pocketed rather than reciprocated. Every. You acknowledge the other's point, the other does not acknowledge yours.

- Emotional intensity is growing.

- The other person is not responding to what you said, but to what they expected you to say. You have become a stand-in rather than a person.

- You are becoming someone you do not like. Someone who scares a dear one.

Attempt anyway?

There are three considerations in whether to engage anyway.

- Strategic withdrawal to preserve resources and waiting for changed circumstances.

- Seed-planting, engaging briefly to leave something behind, a seed that might find fertile ground even if it is in a crack in the rock. This need not be a drawn out conversation. This might be one sentence; perhaps in a note card as I have mentioned elsewhere.

- Deliberate engagement with full knowledge that it will be costly and might not succeed, because the stakes are high enough to justify the cost. Is it worth the cost? I hope to gather info that will help. But, you have to be ready to learn about discourse and take the courageous steps.

Some people will never be reachable by you, and possibly not by anyone. But know this: This is compatible with believing that fruitful dialogue matters enormously. Not every seed lands on good and protected soil, but you don't stop sowing.

Keep on going

Start with those that are not too distant on the ideological map; just avoid too many echo chambers. Talk with people; listen.

Start with limitations in depth (vulnerability), scope (people on the tribal map above), duration, and actionable limitations ("Use that word again and I'm hanging up.")

Look at the persons in your community (home, church, town, nation). What makes each one an individual, special, someone distinct from the another standing to the side?

Fruitful dialogue is best one-on-one. As this blog has demonstrated in posts with the theme common ground, there are things in common between any two persons. If that connection is in the green zone, or might be, go for it.

There are many opportunities.