Morse Code Day!

Morse code is a physical level of communication. As such, it can contribute to fruitful dialogue and even help us learn about communication in general.

This is a good day to write your name in morse code. You can! Keep reading!

Brownielocks came up with a day to think about Morse code. She called it...

Learn Your Name in Morse Code Day

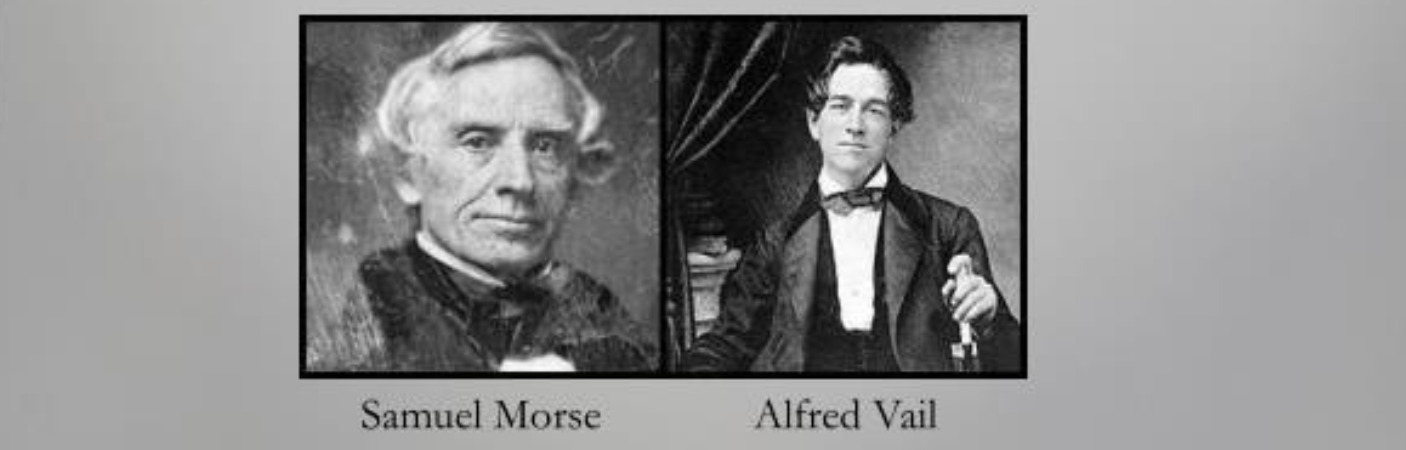

The date, January 11, commemorates the day in 1838 when Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail first publicly demonstrated the telegraph. The New Jersey Historical Society thinks it was on January 6.

Wondering what dots and dashes have to do with fruitful dialogue? Read on!

The Most Basic Layer

When we talk about communication, we often start with what we're saying—the content, the arguments, the ideas. But underneath all of that lies a more fundamental question: How does the signal even get from me to you?

Communication theorists talk about layers. At the top, there's meaning and interpretation. In the middle, there's language and grammar. But at the very bottom, there's something almost mechanical: the physical signal itself. The vibration of air. The marks on a page. The electrical pulse down a wire.

Morse code lives at that bottom layer. It's about as fundamental as communication gets: on or off, short or long, sound or silence.

Di-dah. That's the letter A.

A Partnership, and a Rift

Here's something that doesn't get talked about enough.

We call it Morse code. But there's good evidence that Alfred Vail—not Samuel Morse—designed much of the code system we actually use today. Morse was the visionary, the promoter, the one who saw the potential and secured the big funding. Vail was the engineer, the one who made the thing actually work.

The message through the telegraph has a flaw in the communication of its history, one that is about communication between partners.

The Beauty of Constraint

There's something almost poetic about Morse code. You have exactly two building blocks: a short signal (dit), a long signal (dah) and spaces.

The timing matters:

- One dit-length of silence between the elements of a single letter

- Three dit-lengths between letters

- Seven dit-lengths between words

The constraints force clarity.

This timing is important in Morse code; there are timing constraints. If timing has to be flexible, then a tap code might be needed as in striking a spoon on a pipe. If timing is very poor, some kind of framing is needed.

This is especially important for the Dah, the three-unit ON signal. A percussion method (unmodified) does not work.

I find this instructive. Sometimes constraints don't limit communication—they clarify it.

Try It Yourself

Here's a little tool. Type your name and watch the pattern emerge.

The visual shows you the actual timing—each dit and dah as a rectangle, the spaces between them, the letters underneath. Hit play and you'll hear it: 700 Hz, the classic telegraph tone.

Notice how the encoding is efficient; frequent letters have the shortest codes.

Adaptation

Here's what fascinates me most about Morse code: it adapts to almost any medium.

During the Vietnam War, Navy pilot Jeremiah Denton was captured and forced to participate in a televised propaganda interview. While speaking to the camera, he blinked the word T-O-R-T-U-R-E in Morse code.

In January 1941, Victor de Laveleye, a Belgian broadcaster working for the BBC, had an idea. In both writing (think chalk on a wall) and music we find the letter V, which in Morse code is di-di-di-dah. It matches the opening of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. The BBC began using those four notes as an interval signal before broadcasts to occupied territories.

What Does This Have to Do with Fruitful Dialogue?

Fruitful dialogue isn't just about having the right ideas or finding the right words. It's about transmission. It's about making sure the signal gets from here to there, there to here, clearly enough that someone else can decode it.

When dialogue breaks down, it's often not because people disagree about the content. It's because the signal itself got garbled somewhere.

Morse code reminds us that communication is, at its core, a physical act. It requires someone willing to encode out the message and someone else willing to listen for it.

We will be continue in more posts on the physical layer of communication, person & person, person & machine, and person & person through machine. This is at the signal encoding layer.

Your Turn

So here's a small challenge for Learn Your Name in Morse Code Day.

Use the tool above. Learn your name. Maybe hum it. Maybe blink it to yourself in the mirror.

And then think about this: What other channels do you have available to you? When one way of communicating isn't working, what else might?

💡 Did you try the Morse code tool? I think it is easy.

📡 What channels of communication do you find yourself relying on?

🔦 Have you ever had to find an unconventional way to get a message across?

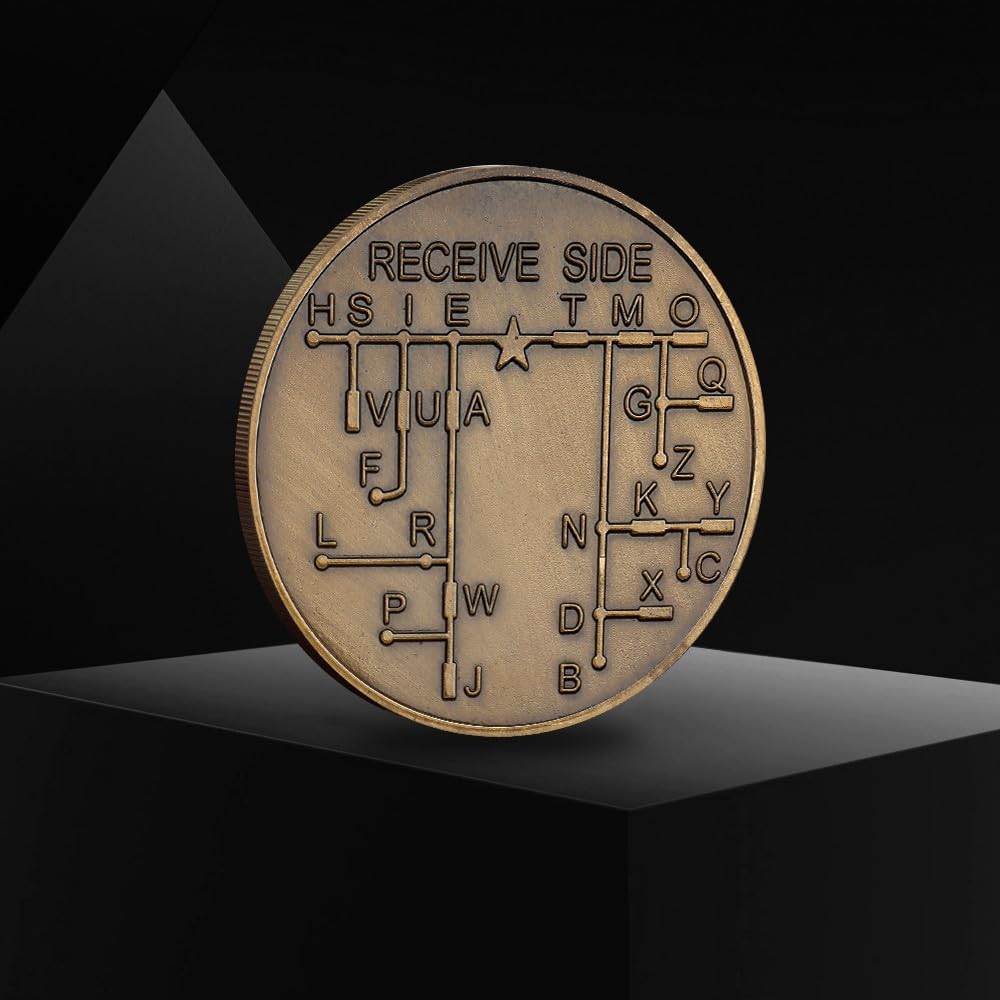

Morse Code Commemorative Coin

Keep this with you and use it as a reference for both sending and receiving Morse code. A Mouth Fruit fan has one.

View on Amazon